Henry Friedman

We have to try to improve ourselves, to be more decent; to try to do the “good thing.”

—HENRY FRIEDMAN

Born: May 19, 1923

City of birth: Oradea Mare, Romania

The Oradea Jewish community had been one of the most prosperous Jewish communities in the Austro-Hungarian empire, and Jews held prominent public positions. The beautiful Neolog Temple on the riverbank towered over the city. Oradea had become a part of the Kingdom of Romania after World War I.

Alexander Friedman, Henry’s father, was an insurance broker, and they lived in a primarily Catholic neighborhood. Henry led a very happy childhood, playing with his Catholic neighbors and older siblings daily. Henry’s parents were not particularly religious, but they regularly attended services at the synagogue, and like all his peers, Henry became a Bar Mitzvah at the age of thirteen. He attended a Jewish school, belonged to Zionist youth groups, and enjoyed book binding and photography.

Henry’s father had grown up a proud citizen of the Austro-Hungarian empire and was initially eager to see Oradea return to Hungary. But 1940 Hungary was not the nation of his childhood, and his excitement was soon lost. The Hungarian government quickly adopted the antisemitic ideologies of the Nazi party, and began passing “race laws” modeled after Germany’s Nuremberg laws. These laws denied Jews equal citizenship status, forbid intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews, excluded Jews from various professions and schools of study, and restricted their economic opportunities.

Henry grew up wanting to be a textile engineer, working hard at school so he could go to a good university. But new laws restricted the number of Jewish students who could attend college. Denied an education, Henry began working as a manufacturing apprentice.

As Henry prepared to leave, he kissed his mother and sister goodbye, not knowing that this would be the last time he ever saw them. His grandmother pulled him aside and led him to away to the other side of the duplex in which they were living. An old man, with a long, white beard and a tallis (prayer shawl) on his shoulders was waiting for him. He raised a second tallis over Henry’s head and placed his hands on Henry’s head. He said a blessing over him; a blessing that, as Henry put it, was: “a shield of protection, which is with me even today.”

Since Henry had a mechanical background, he was sent to a Manfred Weiss Steel and Metal Works, an SS-controlled military production factory outside of Budapest. On his first day, the air raid siren began blasting and everyone ran for cover. Henry and the other freshly arrived Jewish workers followed the crowd to the shelters, but they were told “there’s no room for Jews.” Henry and the other Jewish workers laid down near the fence of the complex, and watched approaching airplanes drop bombs. Such bombardments happened daily at the factory, and Jewish workers were never allowed in the shelters.

Years later, Henry learned that as part of an effort to keep crowds from panicking before they were gassed and sent to the crematoriums of the death camp Auschwitz, Nazis would sometimes distribute postcards and pencils to their victims and let them write a quick note. The postcard was most likely written just minutes before Clara and Henry’s mother were murdered.

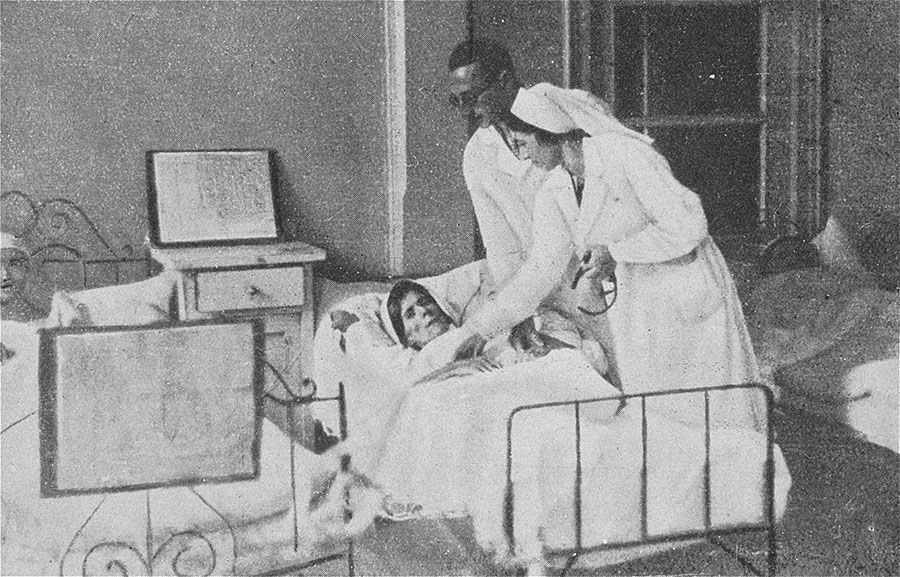

Finally, the factory manager, fearing Henry’s infected wounds were contagious, decided to send him to an army hospital in Budapest. He was given a number and told to wait, but before he could be seen the sirens sounded and the bombing began. The entire hospital was reduced to rubble, and Henry was evacuated to another hospital farther away from the city. Even though he was the only Jewish person in the hospital, miraculously he was still treated like a human being and given food, a bed, and fair treatment.

As the war began to draw to an end, the factory Henry was working in was destroyed by Allied bombing. The Germans overseeing the workers ignored the Swedish passports and put Henry and the other factory workers on a forced march in sub-zero temperatures. Henry’s shoes had fallen apart long before, and he marched in wet rags stuffed with paper for five days, watching countless others drop dead from exhaustion and starvation. On the fifth day a courier came, telling the troops to return the marchers to Pest, where they were placed in a ghetto near the Dohany synagogue, where food rations were provided by the Swedish embassy to those holding the Swedish passport. (Henry later learned that the courier had been bribed by Raoul Wallenberg to send the message).

Henry lost consciousness for a few hours; he assumes he fainted just as the rifle fired. He was shot in the shoulder, but left for dead. He awoke the next morning crushed beneath the dead bodies of the other prisoners, whose warmth had kept him from freezing during the night.

Henry limped from the cemetery back to the civilian hospital. He snuck into the basement and hid in a coal storage room. During the day he remained in the dark, freezing room. At night, he crept outside to scrape snow to quench his thirst. He was starving and feverish from his injuries; he knew he had to find food. Nervous, he made his made way from the coal room and found a morgue, where someone had left a plate of frozen, moldy chicken. This sustained him for a few days.

From the basement, he could tell the war front was getting closer. Finally, he heard Russian being spoken above him and he knew the Soviet Army had arrived. He left his hiding place and surrendered to the Soviets, thinking “the war is over for me.

As he marched, Henry had a moment of near hypnotization. A girl, watching from the sidewalk, caught his eye and, holding his gaze, told him in a whisper “Get lost. Get lost. This group is going to Siberia. Get lost.” Henry slowly slipped from the column until he was just surrounded by civilians waiting to take their goods across the river. He blended into the crowd and escaped across the bridge.

Henry decided to head towards to the railroad station, hoping to find his way home to Transylvania. When Henry was asking for directions, a good Samaritan invited Henry to his home, and gave him a warm meal and a place to sleep for the night. Before Henry left the next day, the man gave him an arm band with the colors of the Romanian flag. The band would result in better treatment from the Russians, as Romania, unlike Hungary, had been a Russian ally during the war.

After a few days, word came that Steven Friedman would be arriving soon at the hospital. Henry was ecstatic at the possibility of seeing his brother again. He arranged to have the bed next to his reserved. He waited eagerly, but in the afternoon someone told him the truth -- the man coming was not his brother, he just happened to have the same name. Henry’s brother had died in a labor camp.

Henry was heartbroken. Everyone and everything he had ever loved was gone. Over time, he discovered that his immediate family had all been deported to a concentration camp, under orders issued by Nazi officials and willfully carried out by local Hungarian police. His father and grandmother died in cattle cars. His mother and sister were murdered in Auschwitz immediately upon arrival.

Before the Holocaust, Hungary’s Jewish population had been estimated at 861,000 people. Estimates on the number of Jewish people who survived until the end range from 80,000 to 255,000. The community was decimated by the war, and no one escaped unaffected. Yet, as he waited to heal in his hometown, where his family had lived for generations, Henry was still surrounded by people who continued to insult Jews, steal their property, and spread lies about their fates. Henry decided the only way to truly heal and maintain his sanity was to leave Hungary and begin a new life.

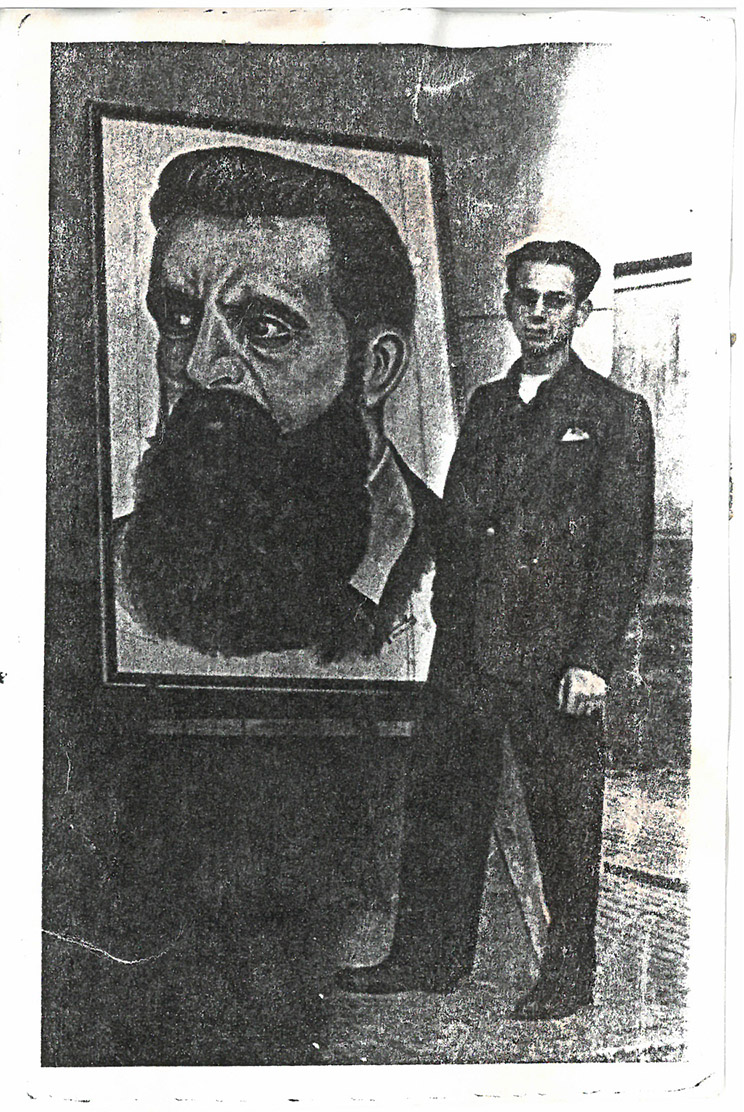

Henry’s grandfather had been a popular fresco artist and had passed down his skills and talents to Henry’s father, who had, in turn, passed them on to Henry. While in the DP camp, Henry became involved with programs to rehabilitate refugees and promote Jewish culture. He painted sets for productions of great Jewish theater, such as plays by Shalom Aleichem, which told humorous stories of Jewish life before the war.

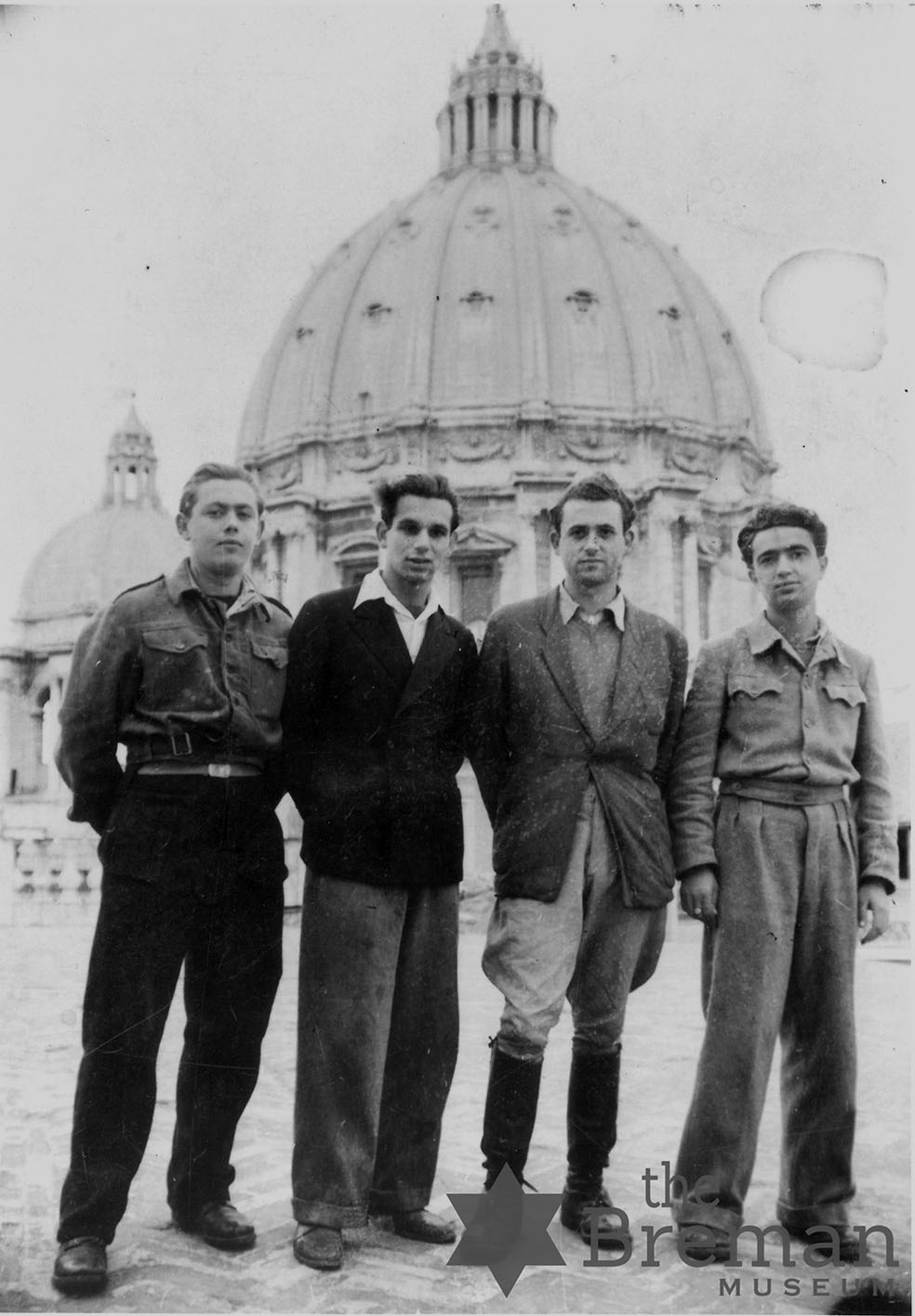

Henry knew he wanted to leave Europe, so he made his way to a big port city. He traveled to Rome, and then Naples and Milan. He made his living as a street artist, painting portraits in tourist areas.

In 1947, he saw an ostentatious movie marquee for Via Col Vento, (Gone with the Wind in English), and went in to watch. In the film, he saw the heroine, Scarlet O’Hara, watch as war burned her city to the ground, leaving her alone in the world. The movie stuck with him, as did the name of the city- Atlanta.

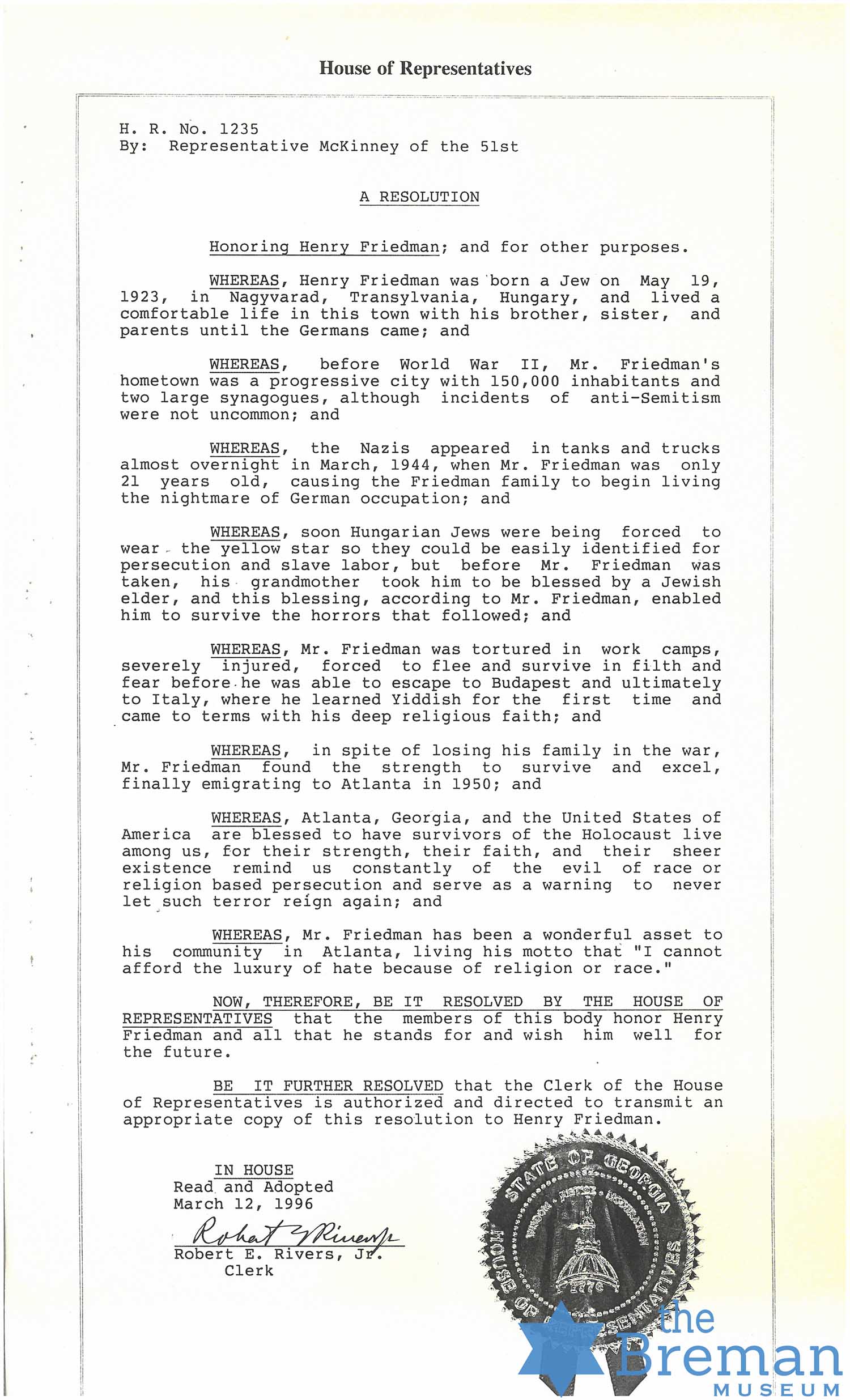

The year Henry arrived, he went swimming at a public beach and saw a sign saying: “No dogs or Jews allowed.” In the 1950s and ‘60s he became increasingly involved in the Civil Rights movement, as he saw the degradation and humiliation shown to minorities in the United States, especially African-Americans, too reminiscent of the horrors he had known in Europe. From his experiences, he knew that no free society had any place for hate, prejudice, or bigotry.

Sherry was deeply involved in philanthropy, politics, and the civil rights movements. She was the first volunteer for the Martin Luther King Federal Holiday Celebration, president of Hadassah, a member of the Georgia Commission on the Holocaust, and a campaign director for Democratic candidates serving at the local, state, and federal levels. For her outstanding contributions, she was honored with the Thomas B. Murphy Lifetime Achievement Award from the Democratic Party of Georgia and was on the steering committee of the 30th Anniversary of the “I Have a Dream” speech and the March on Washington, where both she and Henry were honored. Sherry Friedman passed away on February 4, 2016, after being happily married to Henry for 61 years.

Henry spoke of their effect on him:

“So, all those people in Warsaw—they were sure that the Germans will be victorious, and no one would ever know that people lived and died under what circumstances. They were afraid that everything will be forgotten; everything will be swept under the carpet.

When I read that article in that magazine, that changed all my life. Maybe that was the purpose that I did not perish with my family; I didn't perish with the millions of people. That I had a mission, I had a duty, and I have an obligation, an obligation to speak about it because those six million cannot be here to talk about it.

So even if the subject is a painful subject for me, like pulling a scab from an unhealed wound, I have to talk about it because after my generation is gone, it won't be any first-generation survivors, and will go down in history, and little by little it will be forgotten, forgotten just like nothing happened. And for that reason I feel like I have to do it even if it's not a pleasant subject… Nothing matters but only for me to speak about what happened to those six million Jews.”

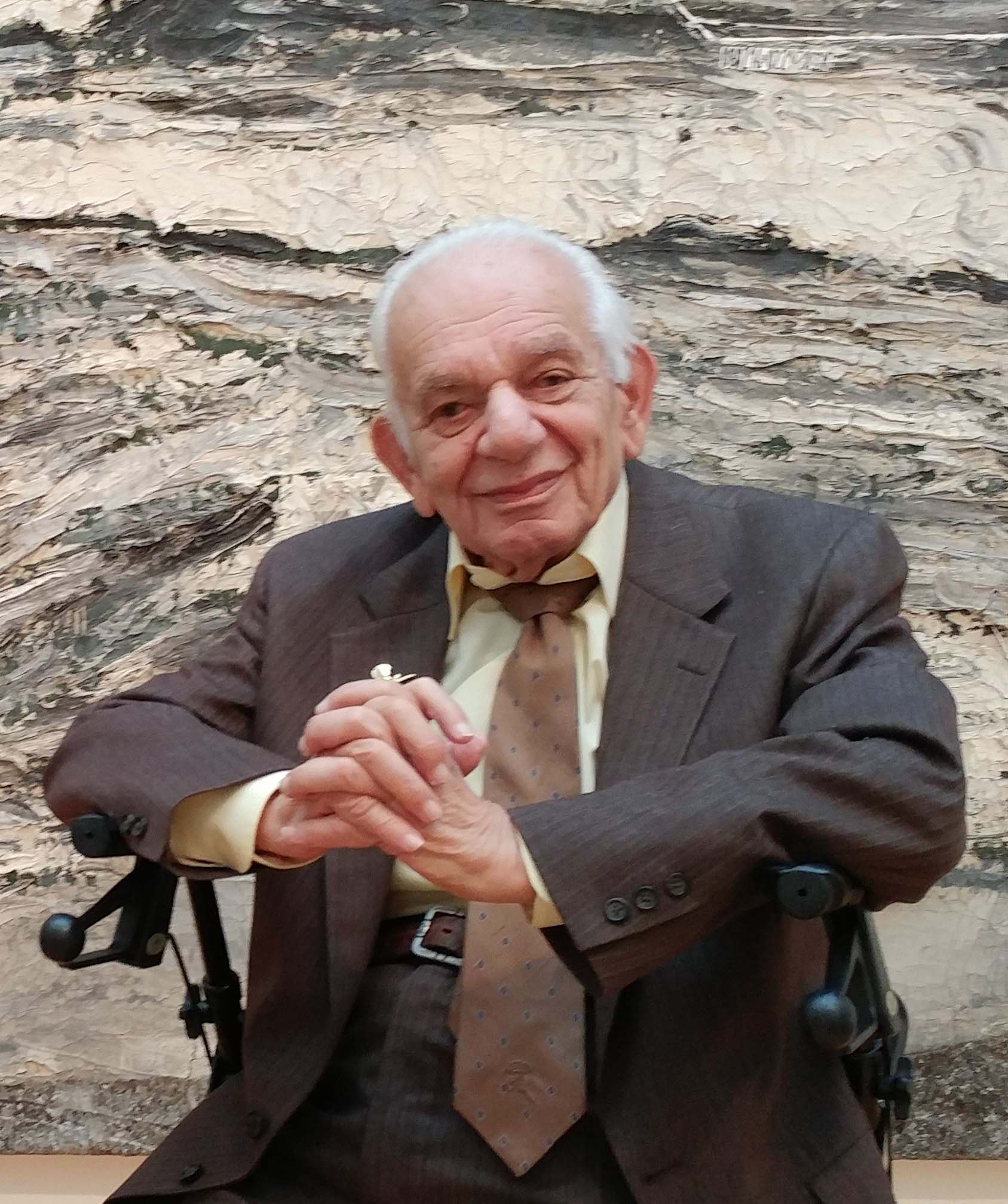

Since then, Henry has spoken to thousands of people, even being honored for his efforts by the Atlanta City Council who declared March 16, 2015 “Henry Friedman Day.”

When Henry was asked what he would have listeners take away from his story, he responded:

“I learned a lot from my wife. She was a very wonderful person, and she was always telling everybody: “There is only one race: The Human Race.” That is what I believe. We are all one race. No individual is better than another one. We have to try to improve ourselves; to be more decent to each of us, to try to do ‘the good thing.’ To try and come up with “what good thing can I do with my time today? What can I do to improve this world?””

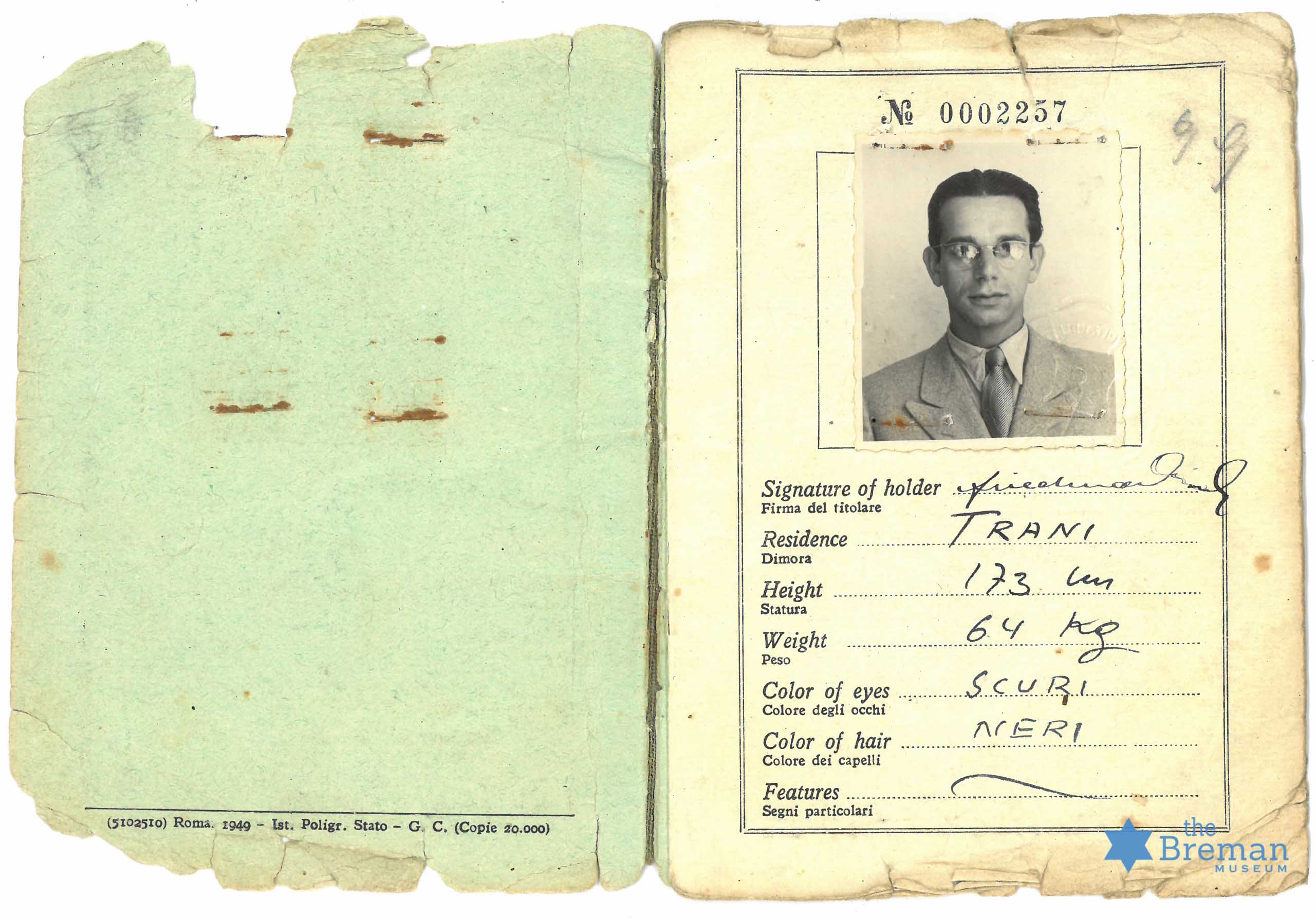

Name at Birth: Imre Friedman

Hebrew Name: Leb ben Shaya

Married Name: Henry Friedman

Parents’ Names: Esther and Alexander Friedman

Sibling(s) Name (s): Clara and Steven Friedman

Spouse(s) Name(s): Sherry (Wolf) Friedman

Children’s Name: Steven Friedman

Date of Birth: May 19, 1923

City of Birth: Oradea Mare, Romania

City of Birth, Alternate Names: Nagyvarad, Hungary

Country of Birth: Romania

Religous Identity (Pre-war): Jewish

Religous Identity (Post-war): Jewish

Ghetto(s), Name/ Year(s): Budapest/ 1944

Camp(s), Name/ Year(S): Manfred Weiss Steel and Metal Works/1944

Liberated By/ Date: Red Army/ February 13, 1945

Location of Liberation: Budapest

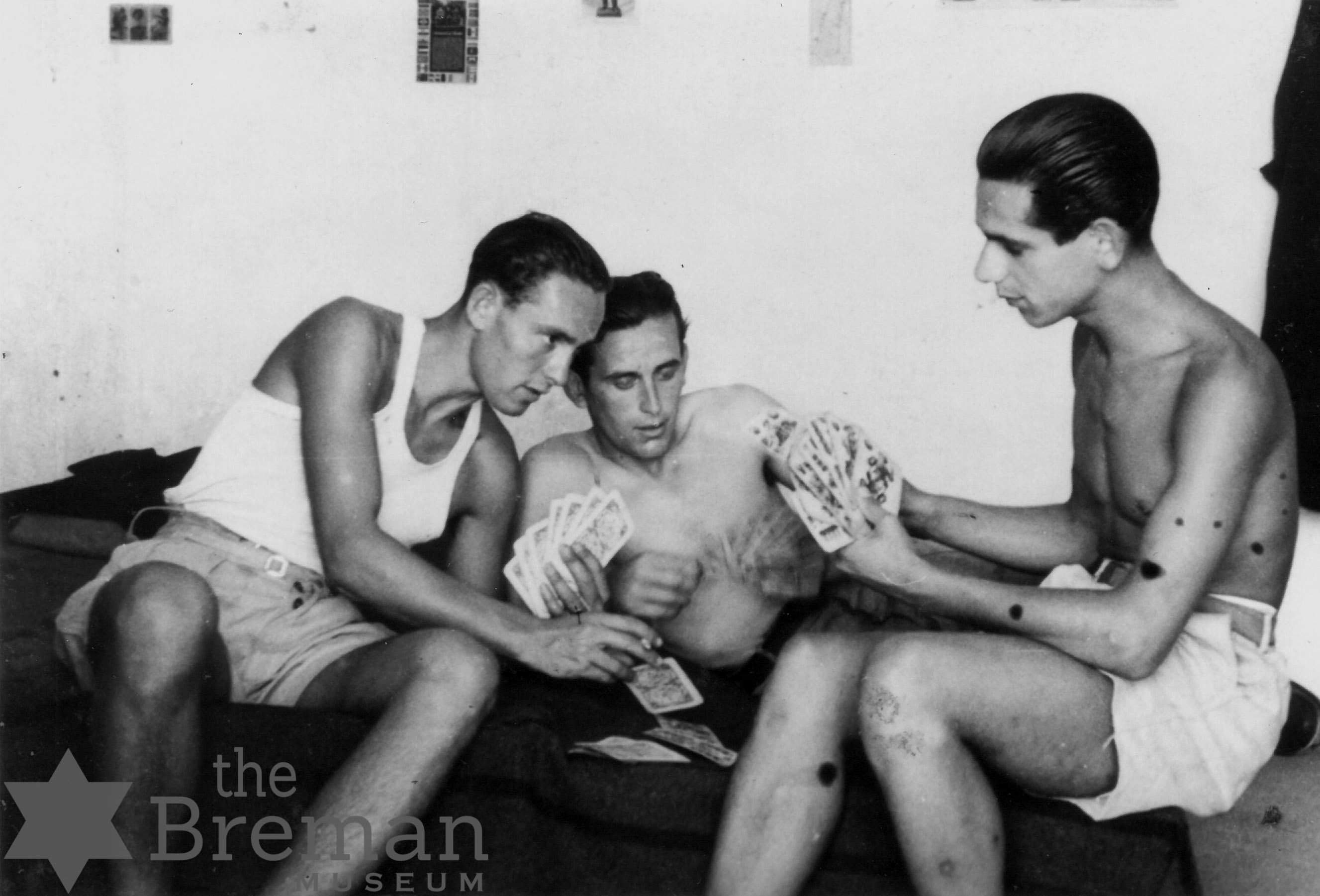

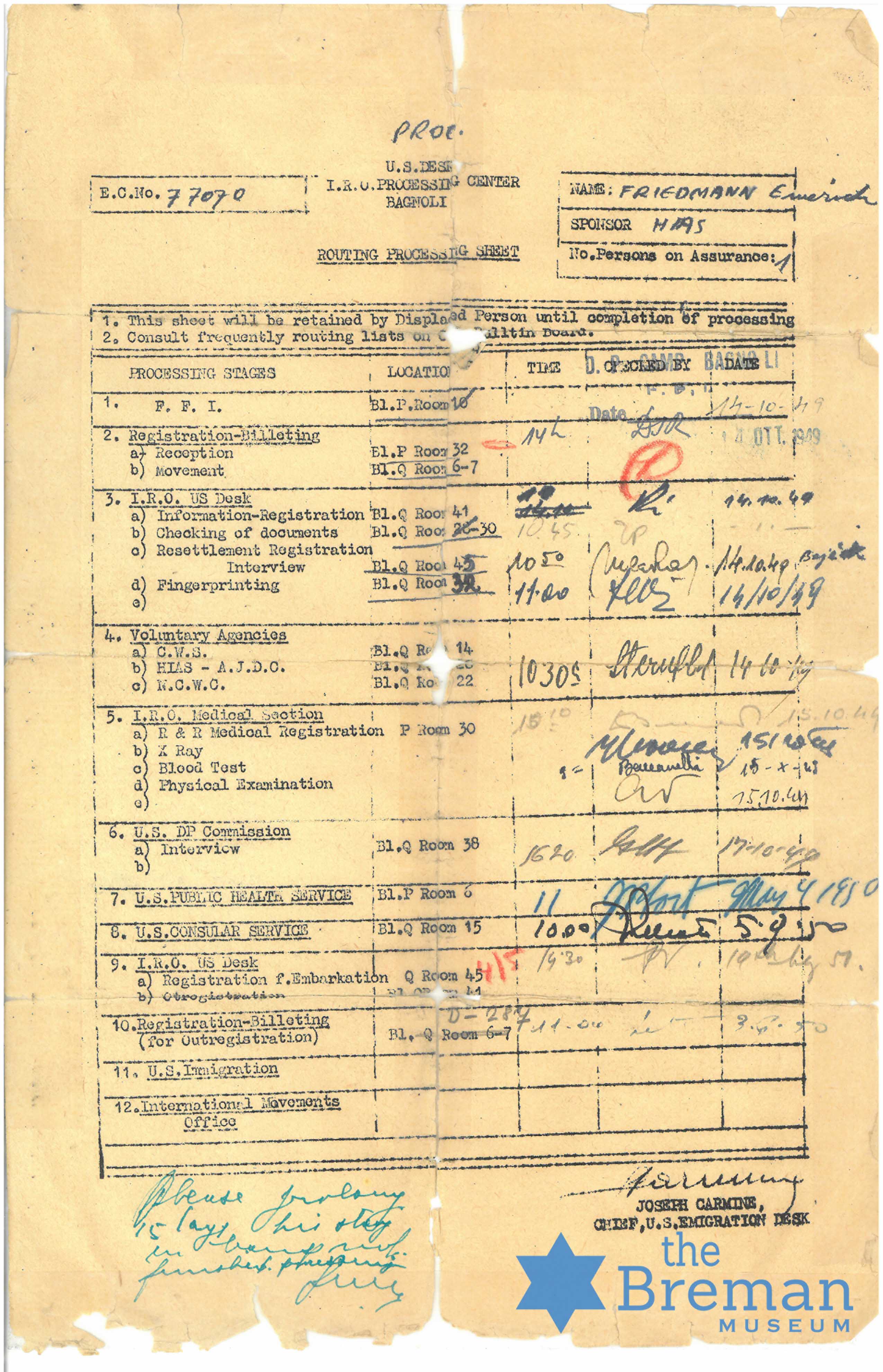

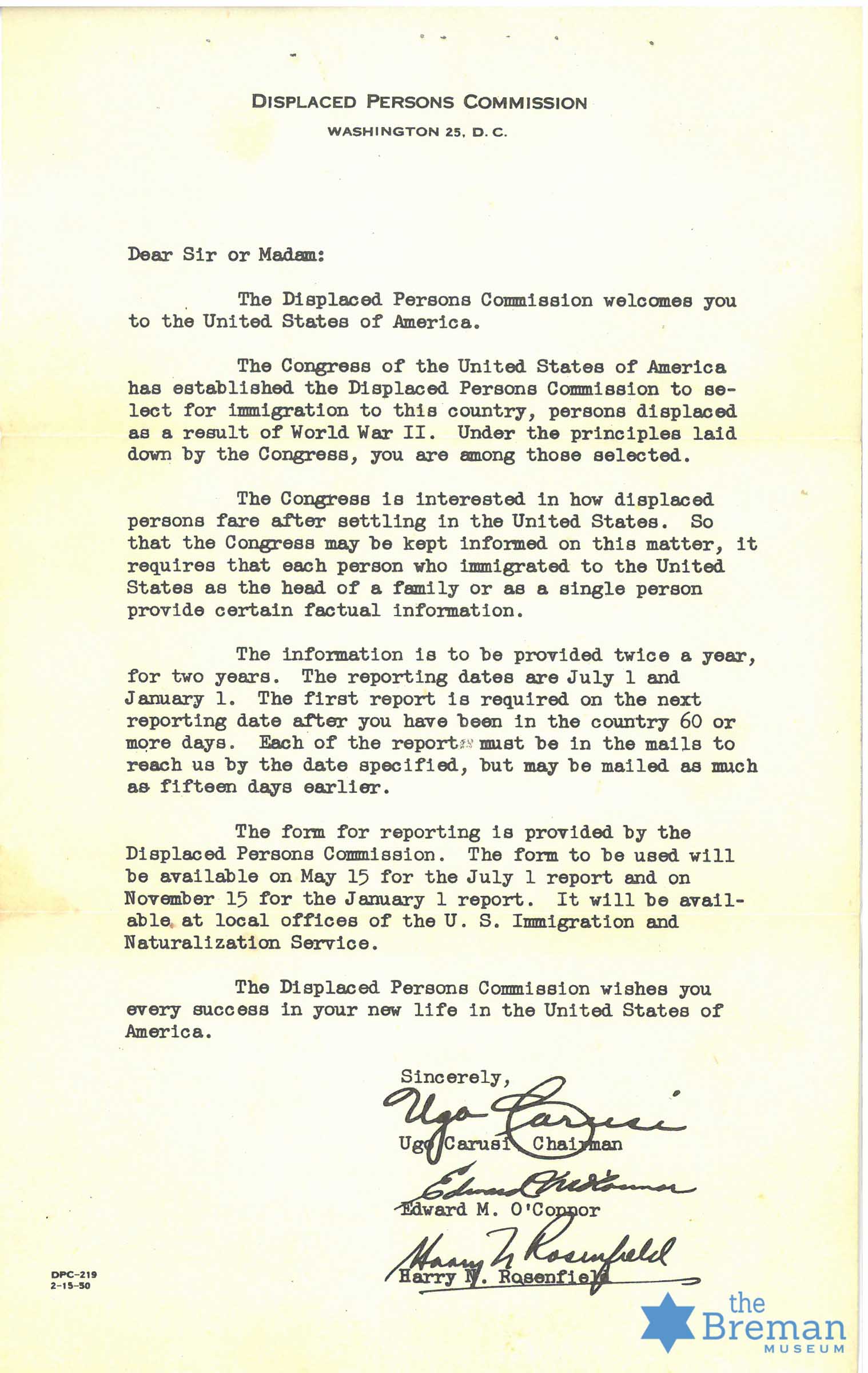

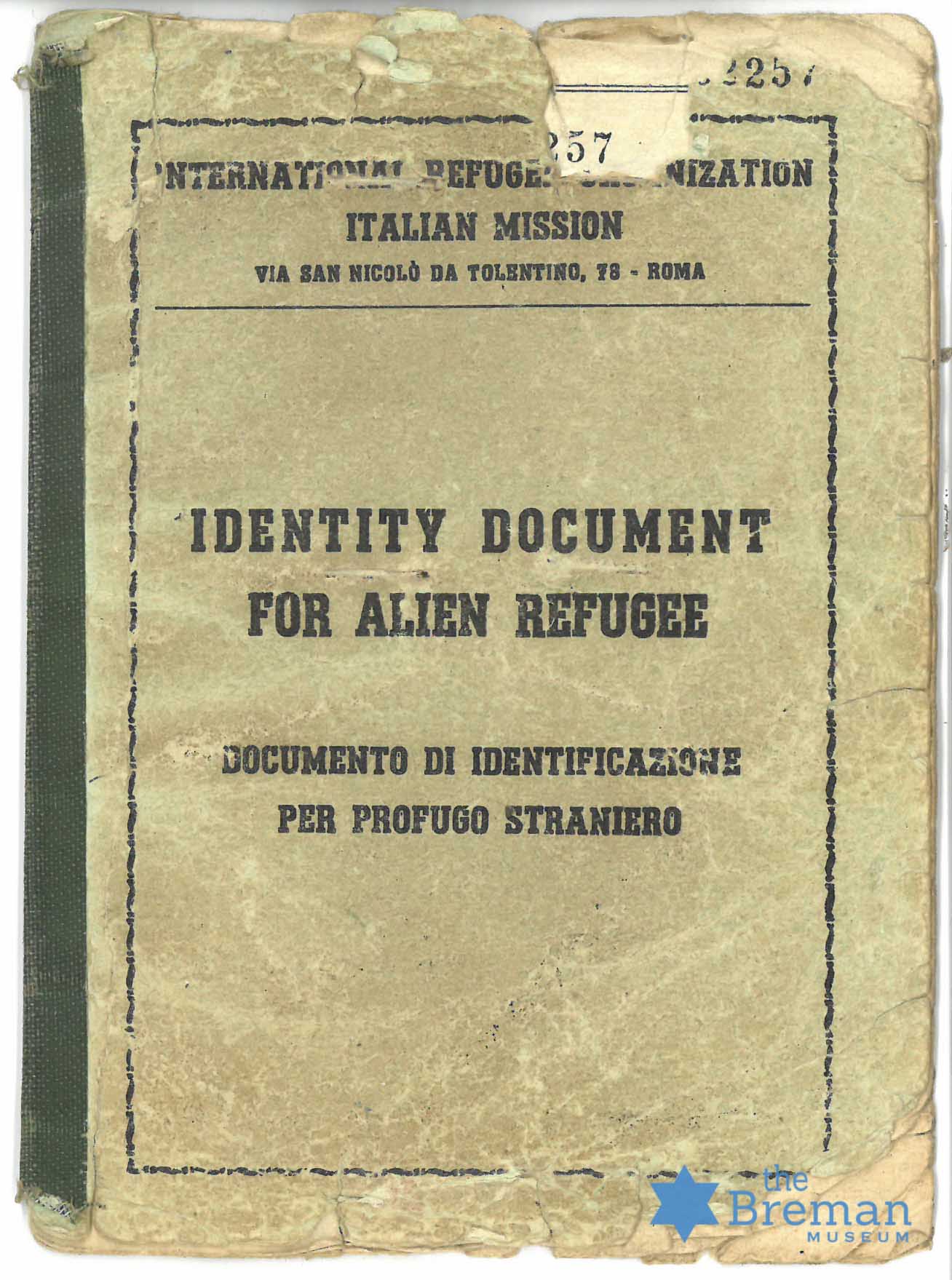

DP Camp(s)/ Year(s): Trani, Italy/ 1946-1948,

Santa Marina de Leuca, Italy/ 1946

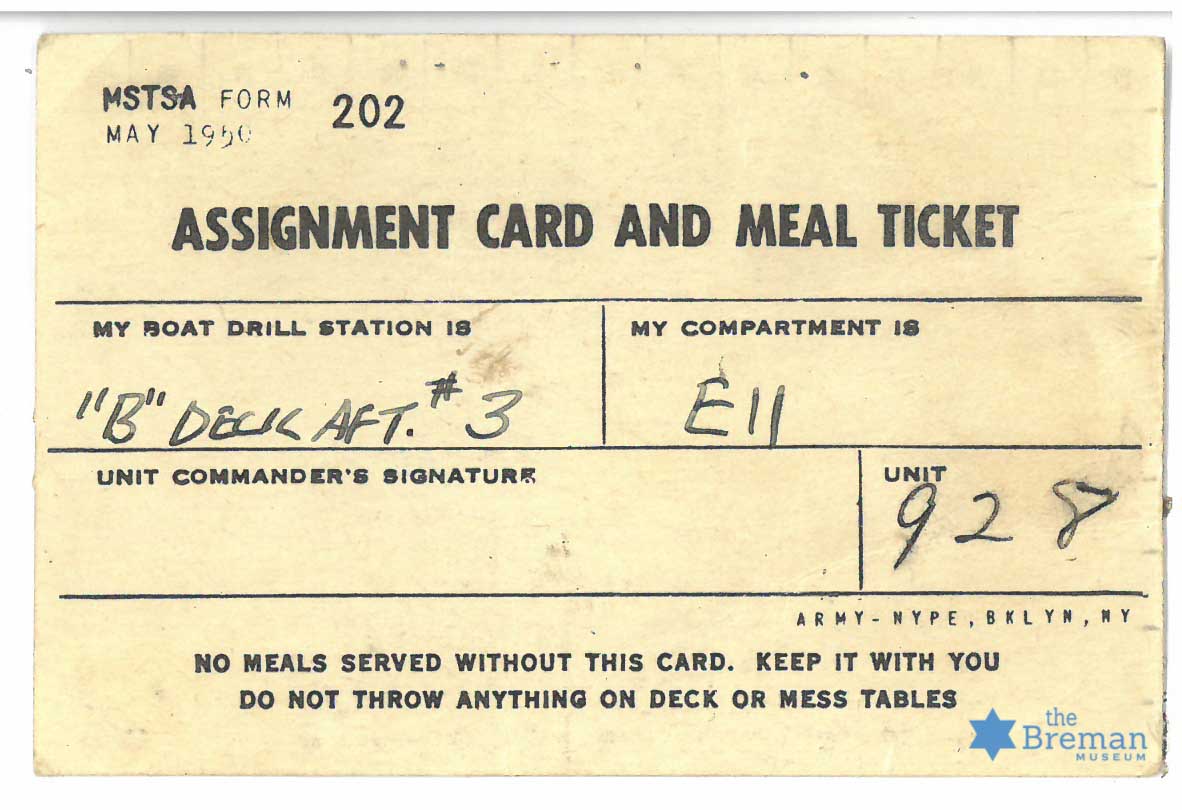

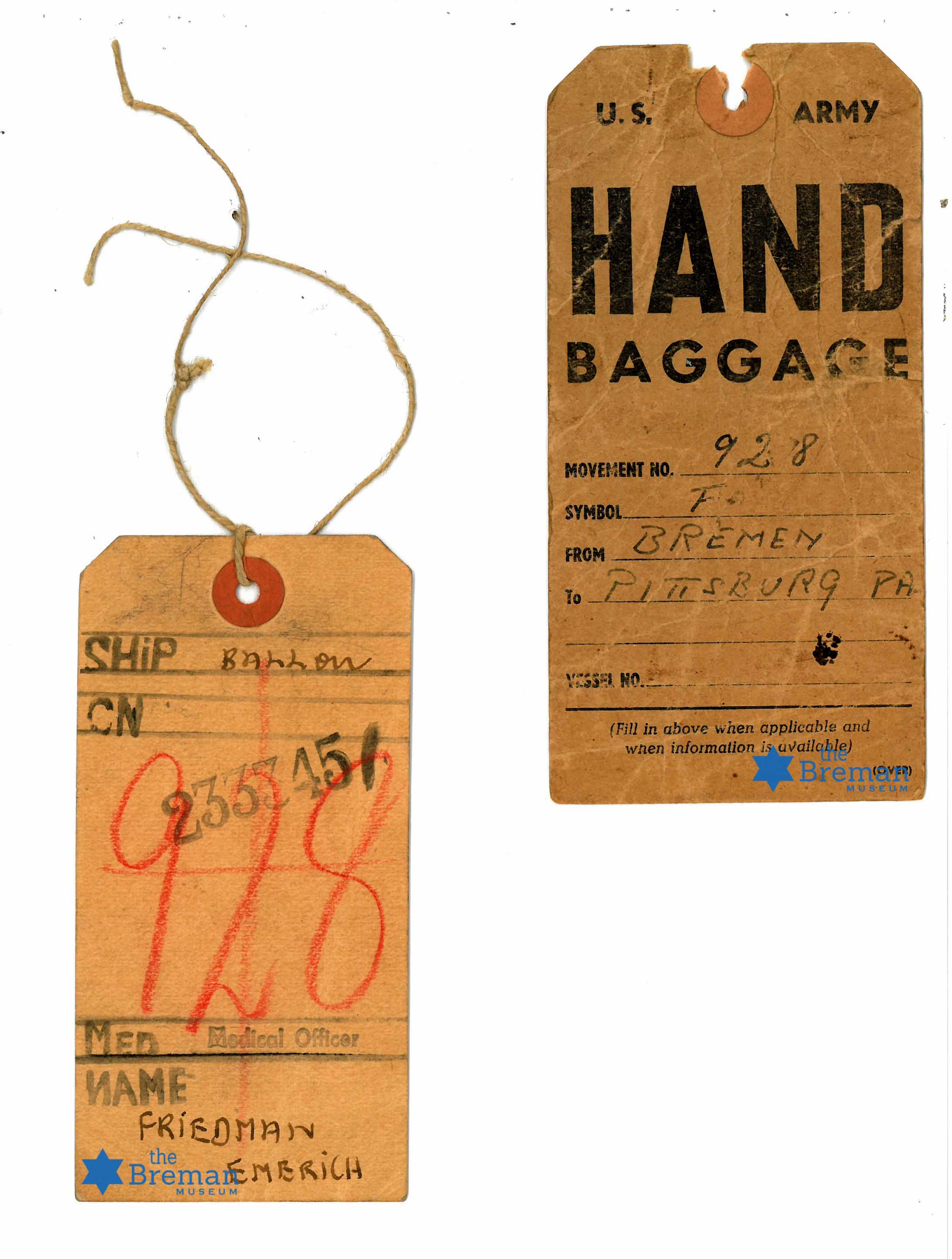

Year/ City/Ship to U.S.: 1950/ Naples to Atlanta/ USS General C.C. Ballou

Georgia City of Residence: Atlanta, GA

Additional Information about Henry Friedman